Feminism in the 21st century ? Woman self portraiture, fashion, cultures, sexuality and other related subjects. CLICK ON IMAGES FOR BEST QUALITY

Showing posts with label "Skin". Show all posts

Showing posts with label "Skin". Show all posts

Thursday, 22 September 2011

Rikke Lundgreen - stills from video

Changing Places, Phil Sayers and Rikke Lundgreen

"Cross-purposes – Looking again at Victorian collections." Sheila McGregor

The implied link between sexuality and death in Segantini’s painting (The Punishment of Lust – 1891) points to one of the most curious and remarked upon aspects of Victorian portrayals of women: the tendency to show the fallen or damaged woman in a state of trance-like immobility. This pictorial and sculptural elision of sexuality, sleep and death has intriguing psychological connotations, hinting as it does at the capacity of women to sustain an interior existence beyond the control and understanding of men. Driven by extremes of experience into a state of emotional retreat, women are simultaneously the victims of male oppression and the agents of their own emancipation, which they often achieve through an act of extravagant self-destruction [as Ophelia and the Lady of Shalott examples].

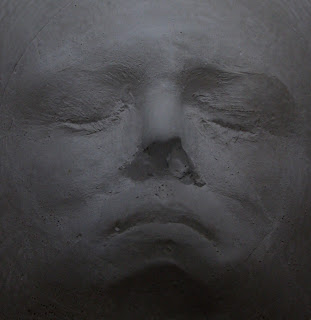

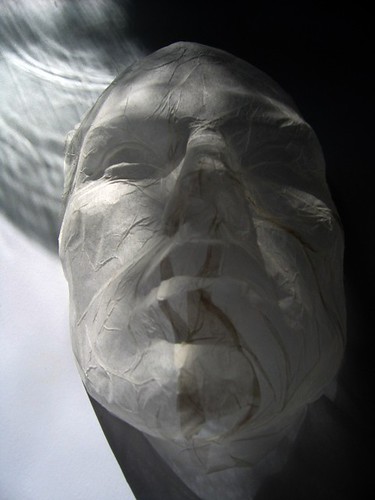

Nowhere perhaps is this theme more strikingly manifested than in sculpture, where the inherent inertness of the stone or marble contrasts with the sinuous realism of the sculptor’s modelling of the female form. Edward Onslow Ford’s Snowdrift (1901) in the Lady Lever Art Gallery personifies the spirit of winter as a naked woman who lies in a pose of exhausted abandon on the icy ground. Conceived in the tradition of funeral sculpture, it is an image that seems to hover uneasily between life and death. Lundgreen explores the thematic ambiguity and erotic languor of the sculpture by re-creating the pose and overlaying images of her own naked body with the original, thus intermingling reality and representation in a way that underscores the virtuosity of Onslow Ford’s sculptural achievement, while also revealing its weirdness as a metaphorical description of winter.

"To pass, Passing and to Come." Lindsay Smith

In [Lundgreen’s] Slow Fade (…), inspired by Edward Onslow Ford’s Snowdrift (1901) we encounter a paradox of of stone (marble) that harbours metamorphosis, change within petrification. The symbolist sculpture made from green onyx, lapis lazuli with silver mounts and black marble achieves its own polychrome, while Lundgreen juxtaposes her own body upon it in polychromatic form. The video morphing of flesh and stone wherebya white marble hand and foot spills out as flesh, is configured with flesh, engenders a simultaneously life-like and yet deathly form.

Wednesday, 13 April 2011

"The New Realism: Pompeii’s Living Dead" By Eugene Dwyer

Brogi 5579. Victim No. 7, in museum case.

From the author’s own collection."Plaster casts of the Pompeian victims, first made by Giuseppe Fiorelli in 1863, have become world famous through post cards, documentary films, and now traveling exhibitions.

Direct exposure to the casts, whether one experiences them in Pompeii or in a museum setting, can be very moving or it can be unaffecting, depending upon the circumstances and expectations brought to the experience by the visitor. To stumble upon a cast unexpectedly in a dimly lighted vault can be a memorable experience.

Fiorelli’s own initial discovery of victims, made by freeing his newly made plasters of the surrounding earth, came as such a shock that he claimed to have “stolen from death” the bodies that had been concealed for more than eighteen hundred years.

In fact, Fiorelli’s process made it possible to see the faces and the helpless gestures of the victims at the very moment they were overcome by the volcano. No one before Fiorelli had seen ancient Romans as “living persons.” Portrait sculpture and ideal or mythological sculpture and painting had been the basis of most people’s acquaintance with the ancients, leading to exalted notions of the beauty of the ancients.

The experience of human remains was limited to skeletons, gruesome but insufficient to contradict the supposed veracity of the works of art. Now it was apparent that the Pompeians had been heavily clothed, mostly well shod, and that they strikingly resembled contemporary inhabitants of the zone. Most noticeably, they appeared to contradict the images handed down in ancient art.

A week after his initial discovery, Fiorelli invited his distinguished colleague, Luigi Settembrini, to Pompeii to view the casts. After a moving visit, Settembrini wrote: “It is impossible to see these three disfigured bodies and not to feel moved – especially the girl with that skull and that body of hers who, being less indistinct than the others, appears to have such grace, that it breaks your heart. They have been dead for eighteen centuries, but they are human beings who are seen in their agony.

“There is nothing of art or of beauty, only bones, the remains of their flesh and their clothing mixed with the plaster. It is the pain of death which has conquered the body and the figure. I looked at the confused mass, I heard the shrill cry of the mother, and I saw her fall and struggle as she died. How many more human beings perished in the same torments and worse!”

“Until now have been discovered, temples, houses, walls, paintings, writings, sculptures, vases, tools, implements, bones, and other objects that roused the curiosity of cultured persons, artists, and archaeologists. But now you, my friend Fiorelli, have discovered human pain, and whoever is human can feel it.”

Where Fiorelli, the scientist, attended to the antiquarian details—the coiffeur, the clothing, the pathology—of the victims, Settembrini, the humanist, recoiled at the evidence of their suffering. Exhibition of the bodies at Pompeii made it possible for viewers to respond individually, and few visitors to Pompeii who recorded their impressions during the late nineteenth century failed to mention a visit to the morgue-like museum.

A growing industry of commercial photography catered to the tourist market, culminating in the picture post cards introduced during the last decade of the century. By then Fiorelli’s casts had become iconic."

in Cultural History,Giveaway,History NF authors,History and Death,History and Nature,History with an H

Eugene Dwyer, author of Pompeii’s Living Statues: Ancient Roman Lives Stolen from Death, was born in Buffalo and attended Frontier Central High School, Harvard College, and the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. After living in Italy for three years, he completed his doctoral dissertation on the use of sculpture in the houses of Pompeii and began teaching the history of art at Kenyon College, where he is currently Professor.

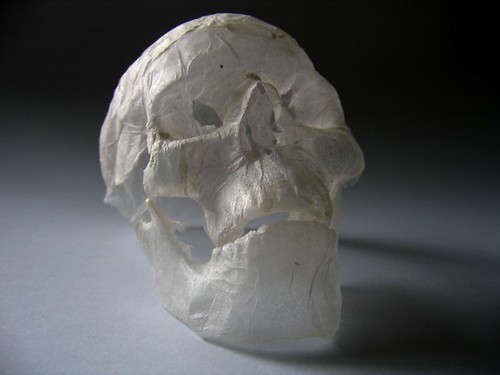

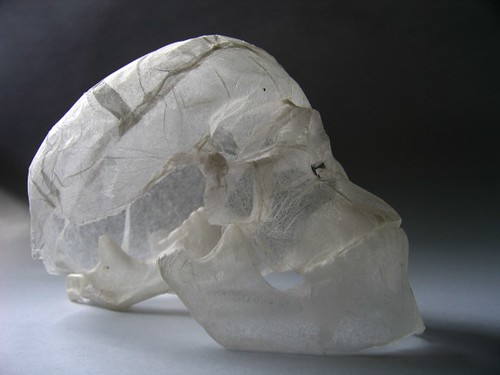

Skin, a porous membrane ...

"Skin is the surface or the boundary line of the body's limit. The skin is actually this very porous membrane so on a microscopic level you get into the questions of what's inside and what's outside. Things are going through you all the time. You really are very penetrable on the surface; you just have the illusion of a wall between your insides and your outside."

Kiki Smith, quoted in an interview April 21st, 2006

Kiki Smith, quoted in an interview April 21st, 2006

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)